Freedom is a slippery concept. At a physical or philosophical level there are many who deny that it exists at all. Spinoza, for instance, thought it didn’t. “Men believe themselves to be free, simply because they are conscious of their actions, and unconscious of the causes whereby those actions are determined”.

Yet it is hardwired into us to feel we are in control of our decisions. Not for nothing do the words “I am the master of my fate: I am the captain of my soul.” from Invictus by William Ernest Henley resonate so strongly.

But we are happy to hand over the decision making process in many areas of our lives depending on our level of competence. It starts as children – no-one expects a child to be at liberty to do what he or she pleases and the same goes for people who are incapable: the mentally ill, severely disabled or people who require assistance. Drawing on the resources of the state involves a gatekeeper and the limits of a person’s ability to live a full life can be largely determined by the decisions the keeper of resources takes.

It seems there is a deep tacit understanding that the gatekeeper in question is another human being; a person who can bring their empathy and emotional insight to bear on the decision making process. We give up freedom, only because we expect to be treated fairly as and by a fellow creature.

But what if that isn’t true? What if the gatekeeper is a machine? An artificial intelligence optimised to provide the best possible decisions for the case in question.

Are we as happy to hand over our liberty to a machine as to a person?

Does it depend on the outcome? If the computer says ‘no’ have I lost my freedom, but when it’s beneficial to me I’m still free?

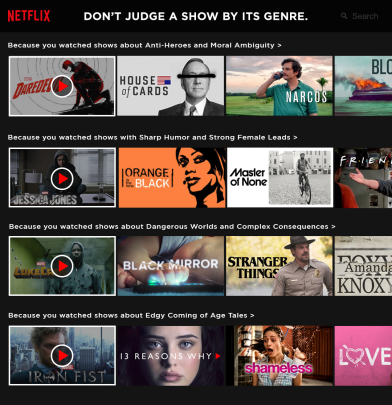

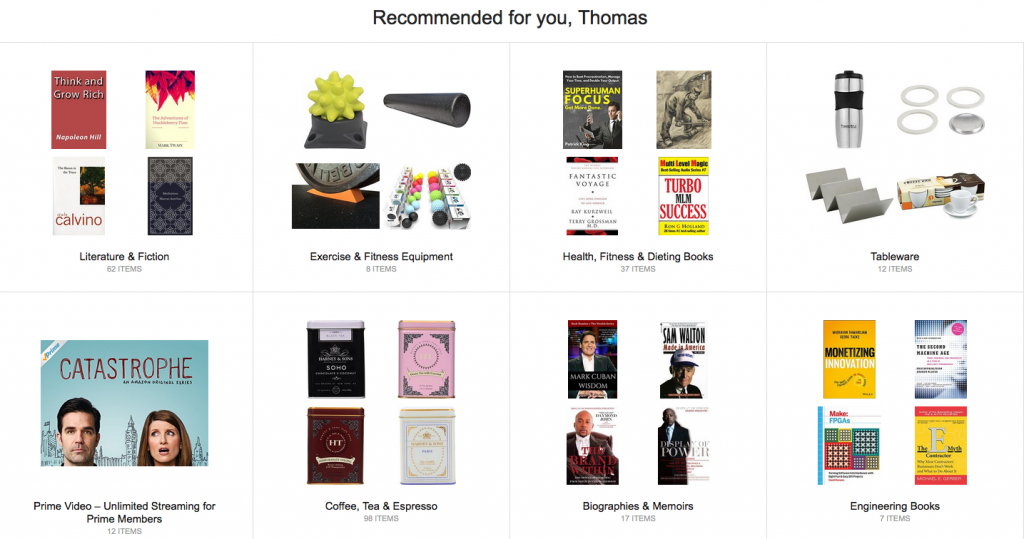

There are subtler effects in play as well. Consider the role of the ubiquitous recommendation engines. Based on your past history and that of all other users, they build a picture of what you will most likely do in any given circumstance. The actual recommendations they make are always optimised to the desired outcome for the organisation providing the service.

Recommendations are not necessarily part of any gateway service. They are usually a form of artificial advice. And in the end people can take that advice or leave it. Whilst this is fair and true, the reality is that most people are tired and lazy. The majority take the easy option. Everyone who works with search engines knows that the result in first position draws the most clicks even when it isn’t relevant to the user’s query.

If most people watch the first recommendation that a streaming movie platform offers them and if that is derived from choices that other individuals have made, to what extent have those individuals chosen freely themselves?

Picking the film you were basically told to pick by an AI system is probably not a big deal. Most of the time the worst thing that happens is a lousy movie, but recommendations can have serious negative impacts (suggesting images of self-harm to a vulnerable teenager for instance).

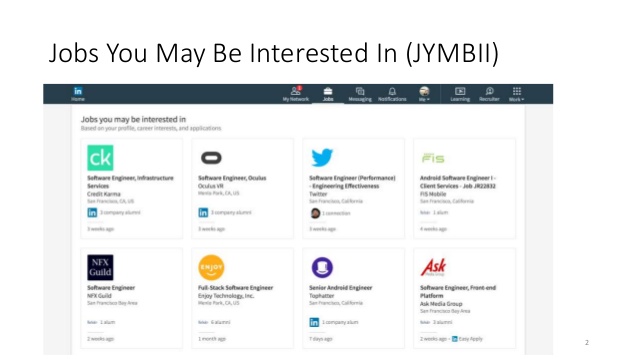

Recommenders can also influence major life decisions like choosing a job. Imagine a recommendation engine on a job board that has a bias towards jobs in out-of-the-way places. Applying to the first job suggested could have a big impact on someone, especially if the jobs in their own hometown were never displayed to them. The effect is often self-reinforcing: once you have expressed a preference in one direction the system will be more likely to replicate that choice.

This might not seem like a big deal, but what if the recruiter on the other side is using an artificial intelligence to screen candidates for interview? You now have a situation where the majority of people who can be hired have been through at least two stages of machine-based decision making. All well and good you might say, this will guarantee that companies have employees who fit better into their roles.

Now this may be true (and probably is considering how much investment is being made on building the technology), but here’s the critical point: in the situation where everyone is happy because the machine takes the decisions, what is the role of human freedom?

That is the topic this blog will focus on. I will post about new technical developments where AI encroaches on human decision making, about efforts to regulate the impact of AI, about philosophical debates on the ethics and realities of the situation and finally (in acts of unbridled self-promotion) I will draw attention to one of my passions which is writing science fiction, because often the best way to handle ethical topics is to examine them under the microscope of the imagination.

These posts will act as subject matter and stimulus for those short fictions and will also look at how likely it is that the scenarios portrayed in the stories could actually happen.